A 7-step plan and template to end preventable Asthma Attacks and Deaths in 2024

An asthma attack means that medication is not working ; it is a red flag. Urgent action can prevent future attacks.

Reduce asthma attacks and preventable deaths by recognising and dealing with modifiable risk factors. Common risk factors for asthma attacks include: excess prescriptions and use of reliever inhalers; insufficient or no prescription of inhaled corticosteroid preventer inhalers; poor inhaler technique; exposure to triggers like non steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; smoking (including vaping).

Another potentially preventable child asthma death!

A coroners inquest concluded in November 2023 that another child had died in the United Kingdom from asthma and that this was a potentially preventable death. This case has really saddened me and stimulated me to do a podcast and also suggest a way that general practitioners can change their practice to ensure all doctors and nurses caring for children particularly are up to date with and have the necessary competencies to manage asthma attacks and the chronic illness. (Please see below for links to the podcasts and the Youtube lecture)

Asthma is a chronic ongoing disease characterised by flare ups of poor control called exacerbations or attacks. These attacks are important risk factors for future attacks.

Asthma attacks are good predictors of future attacks. Good disease control can prevent attacks. So it is logical that we can use attacks as a stimulus for change by learning why these attacks happen by identifying modifiable risk factors – and then dealing with these to prevent future attacks.

See the 7-step plan on youtube and the related podcasts.

Other resources and information include :

- Table 2-2 in the GINA report

- the audit study that showed that hospital admissions can be reduced as a result of post-attack reviews.

- the link to the form below which is a practical example of the questions that can help General practitioners reflect on their care and consequently identify where action is needed to protect patients from poor outcomes

- The recommendations of the National Review of Asthma Deaths in 2014 (NRAD) report are still relevant – these were summarised in my article

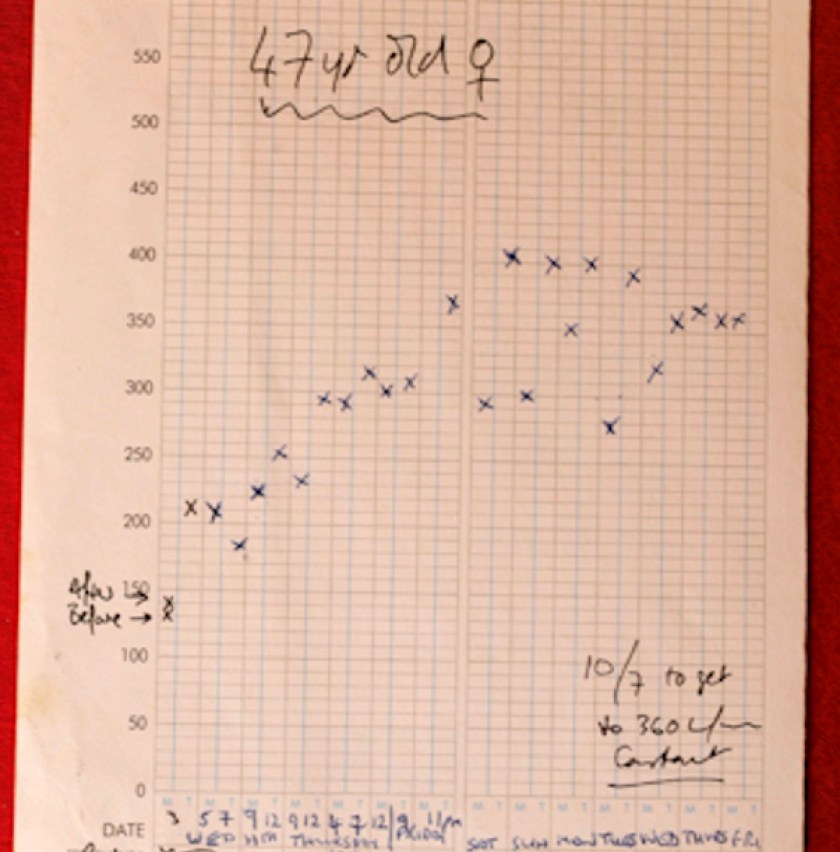

A practical example of a template to analyse patients records

A practical example of a template to analyse patients records after they had an asthma attack. It helps to quickly identify any modifiable factors that could have led to the attack; these should then be dealt with . Please also listen to my podcasts nos 50 (Asthma – a tragic death of a child) and 51 (A 2024 plan to end asthma attacks) and also watch my talk on Youtube to explain the 7-Step Plan to facilitate the process of improving asthma care, reducing attacks, and reducing practice workload.