Introduction

First Aid Asthma information should be widely available. An asthma attack is a medical emergency. It should be taken very seriously. Asthma attacks are also known as flare ups or exacerbations. When someone has an asthma attack, many people don’t know when or at what stage to call for emergency help. In the UK National review of asthma deaths (NRAD), nearly half of those who died had not called for or got help when they were dying.

In the NRAD 45% of those who died did not get medical assistance

We will never know why those people did not get medical assistance when they were dying from an asthma attack. Clearly many had not been provided with an asthma self management plan. However, even some with a plan and still they did not call for help. I think it may have been because they were not clear when they should have called for help.

Personal asthma self management plans need improvement

Clear instructions on calling for emergency help not often included

Many plans do not clearly state when emergency assistance for someone having an asthma attack is needed. Personal asthma action plans (PAAPs) provide information on asthma. Including its medication, how to recognise danger signs and what to do in asthma flare ups. However, most plans include information on when to call for help. Listen to my podcast on emergency help for people with asthma and members of the public here also available on spotify and Apple Podcast platforms.

One size does not fit all – Asthma education should include details on

- What asthma is and how it causes problems for you

- What triggers (or sparks off your asthma attacks)

- What is your treatment, how does work in simple terms, and when you should take it.

- You need to know how to use your inhaler.

- How do you know when your asthma is going out of control or flaring up.

- What do you need to do when it does flare up and of course what medication to take.

- You also need to know when to worry and when you need to call for medical assistance.

- Most importantly you need to know when to call for emergency help.

Therefore provision of asthma education to prevent flare ups needs expertise!

People with asthma need lots of information on their disease. For that reason training, expertise and sufficient time is needed for anyone delegated to teach patients. Expertise is needed to provide asthma self management plans for patients and parents of children with asthma. The tasks listed above do not all have to be provided by one individual. For example, inhaler technique could be taught by a pharmacist who has had training.

Different personal asthma plans should be tailored to individual needs

In the UK most general practice computer systems have only one template for personal asthma plans. As I have noted in this blog, ‘one size does not fit all’. One single ‘off the shelf’ template of a personal asthma management plan cannot contain all the information needed to manage every patient’s asthma. To put it another way, I think there should be a suite of different asthma plans each with a different purpose. Some examples of different plans are:

- A general asthma self management plan for children or for adults and adolescents

- A plan for Maintenance and Reliever Therapy (MART), see here for a description and an example.

- A plan for ‘As Needed Anti-inflammatory Reliever (AIR) Therapy’, see example

- A ‘Three step Asthma Plan’, see example

So there are many different types of asthma management plans!

A special plan – First AID for asthma flare ups

General training on first aid is widely available. In addition training in resuscitation is available in fact its compulsory for all health care professionals and key people in organisations. However, Asthma First AID training is not widely available for asthma – an asthma attack is a medical emergency. Its important to realise that asthma is the commonest chronic childhood disease and affects about 7% of adults. Asthma attacks could and do happen in public places. It follows that First Aid Training for managing asthma should be compulsory for organisations, schools and public recreation facilities.

Examples of Asthma FIRST AID posters and plans:

Some examples of First Aid for Asthma are shown below. Easily accessible information is needed to enable a member of the public to assist them. Specific features needed in an Asthma First AID plan- the australian one is an excellent example

- National Asthma Council Australia, link here. There is one for adults and adolescents, and one for children under 12. The under 12 one includes use of a spacer with and without a mask.

An example of an Asthma First Aid Plan for children which includes use of a spacer with and without a mask

Reproduced with permission from the (c) National Asthma Council Australia. https://www.nationalasthma.org.au/asthma-first-aid accessed 5th September 2023

An example of an Asthma First Aid Plan for Adolescents and Adults

Reproduced with permission from the (c) National Asthma Council Australia https://www.nationalasthma.org.au/asthma-first-aid accessed 5th September 2023

Carers and parents should be provided with clear emergency instructions

Clear specific indications for calling for emergency help for someone having a severe asthma attack should be available for anyone responsible for day to day care of people with asthma. This also applies to the workplace, schools, public recreation facilities.

Conclusion

When to call for emergency help for a life threatening asthma attack

An asthma attack is a medical emergency because this is a signal that something serious has gone wrong. So anyone who has had an asthma attack needs a detailed assessment, in other words a post-attack asthma review by someone trained to do so. The purpose of the review is to identify any modifiable risk factors and deal with them to prevent future attacks.

Clear instructions are needed

Identify the red flags for emergency asthma assistance. In my view this should be very clearly stated in all asthma self management plans and Asthma First Aid Posters and infograms. My ‘Top 3 List’ of red flags below could be used in addition to any advice from the patient’s own doctor. The problem is that someone having a severe asthma attack may not have any of the signs or symptoms associated with severe attacks – so call for medical help if at all concerned about an asthma flare up!

- The short acting reliever (usually blue ie salbutamol, albuterol, terbutyline) should last for at least 4 hours – So the first thing the plan should state is: I need emergency help if my blue short acting reliever is not helping my symptoms or if I need it again within 4 hours.

- Next, waking due to cough, wheeze, breathing difficulty and shortness of breath is a danger sign. So next, I need emergency help if I’m waking up at night with cough or wheeze or shortness of breath

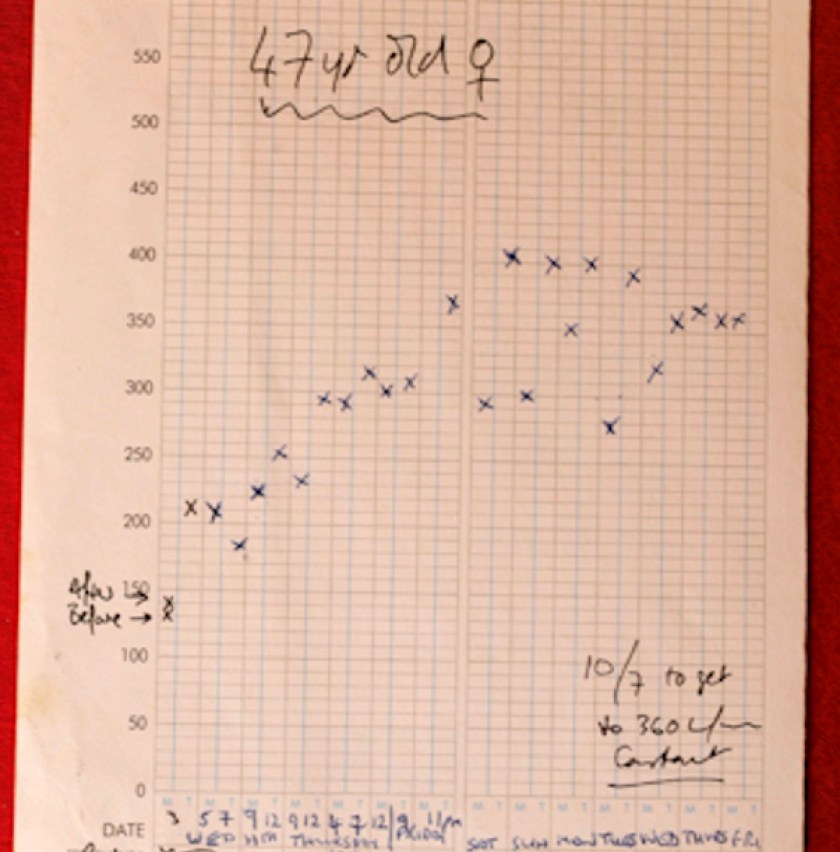

- Many people have their own Peak Flow Meter and if you have one: I need emergency help if my peak flow rate falls below 60% of my best : Enter best x 0.6 = (l/min)

Then the additional item on this emergency plan should be about what you tell the emergency services: What you tell them will determine how rapidly emergency assistance is dispatched:

Information to include: That the person has asthma; say if they have breathing difficulty; and to say if they are waking because of asthma; say if the reliever is not working; and if they can do Peak Flow, what their reading is now and what their best reading is.